Hayes Gallery

Six Emerson Burkhart Paintings from the Hayes Family Collection

Emerson Burkhart: Impassioned Artist, Thinker, Crusader

We are pleased to present to you Paintings by Emerson Burkhart from the collection of Ben Hayes (1912 – 1989). Ben was an award-winning journalist and columnist with the Columbus Citizen and the Columbus Citizen Journal for more than 40 years. He also served as a restaurant critic for many years and was a well-known fixture around Columbus.

Hayes was also an integral part of Burkhart’s large circle of media personalities who gave the artist substantial free press pertaining to his art activities around town and, later on, around the world.

Hayes would faithfully promote Burkhart’s annual open house art sale with multiple columns in the weeks leading up to the event. Burkhart leveraged these relationships, and as a result, he became one of the most recognizable personalities in Columbus during the 1950s and ’60s.

Hayes and Burkhart were close for many decades, and aside from their professional relationship, were best of friends, visiting one another frequently. As you will read further on, during the last fifteen years or so of the artist’s life, Burkhart spent almost every birthday at Ben’s house for a wonderful home-cooked meal and lively discussions after dessert.

For more information on the life and career of the late Ben Hayes, we direct you to the Ben Hayes Scrapbook, a soft cover publication that he wrote after retiring from the Columbus Citizen Journal. It is long out of print, but copies may be available on the internet.

Lucian Hayes with his mother, Christine, at the Hayes home In Worthington, Ohio

About the Hayes Burkhart Collection

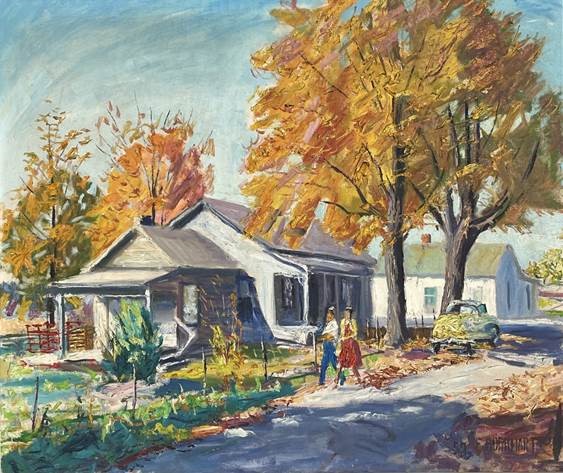

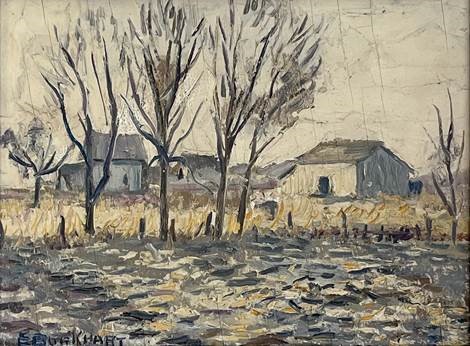

Burkhart was generous with his close friends and often gave them paintings in exchange for the valuable publicity they provided for the artist. At least one of these paintings is Blacklick, Ohio (1957), a large landscape of two buildings with figures in a fall setting, featuring colorful autumn colors in the trees set against a clear blue sky. This property, on the east side of Columbus, was owned by the Hayes family.

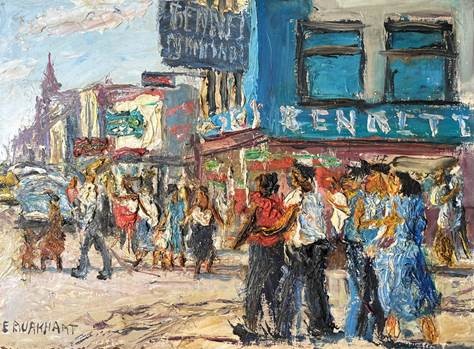

Three other works in the Hayes collection by Burkhart — Street Corner (1956), Portrait – 1960, and The Farm (1956) — in addition to the aforementioned landscape, Blacklick, Ohio, were all included in the “Burkhart Retrospective Exhibition 1970-1971” at the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts (now the Columbus Museum of Art – CMOA). Two other Burkhart paintings were part of the family connection and are also included in the Hayes Gallery.

Lucian Hayes with his mother, Christine, at the Hayes home In Worthington, Ohio

About the Hayes Burkhart Collection

We are grateful to Lucian Hayes, grandson of the late columnist Ben Hayes, for allowing us to include his family’s holdings by Emerson Burkhart in this special gallery. As the last surviving member of the Ben Hayes family (and yes, they were closely related to OSU football coach Woody Hayes), Lucian has been painstakingly working his way through endless family material that was saved for generations by his paternal grandfather. We are working with him to ensure an appropriate home is found for much of what he has uncovered so that it may be enjoyed by future generations of Central Ohioans.

As for the Burkhart paintings from the Hayes collection, we hope you will enjoy them as much as we do.

A Tribute Only a Daughter Could Write

Ben’s late daughter, Christine, wrote a glowing tribute to her father on the 100th anniversary of his birth. Her piece appeared online in the Columbus Bicentennial blogspot, April 1, 2012.

It provides a great snapshot of Ben Hayes’ life in Columbus as seen through the eyes of his only daughter. We reprint it here to share additional context on the man who attracted many friends, including our favorite artist, Emerson Burkhart.

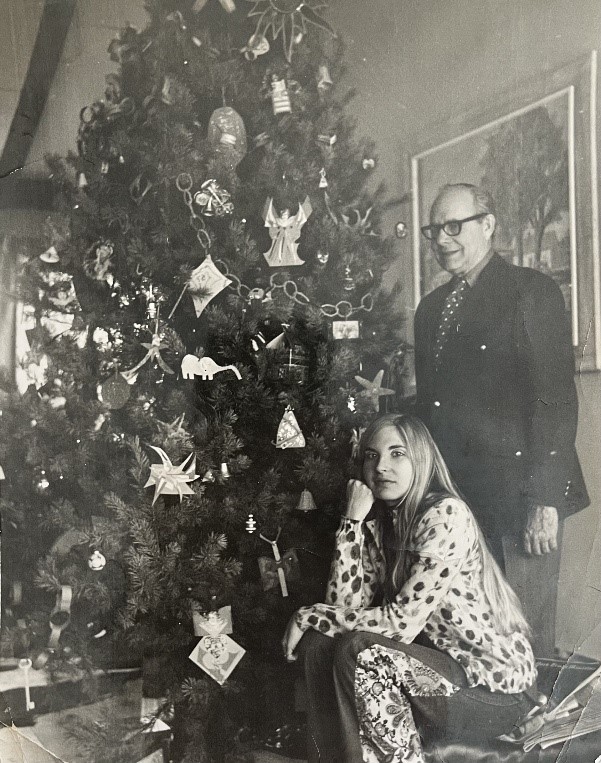

Ben and daughter Christine celebrating Christmas in the 1960’s

Ben Hayes

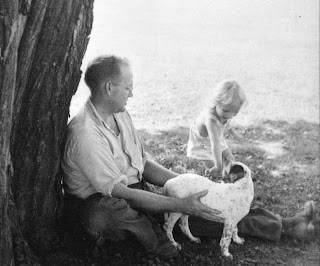

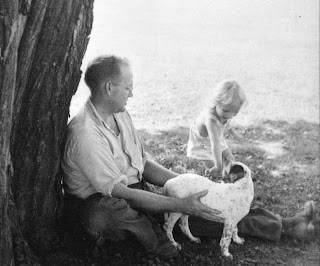

Ben and Christine enjoying a summer afternoon

Ben Hayes’ One Hundredth Birthday, April 1, 2012

By: Christine Hayes

The sound of his Underwood: keys punched, the bell, carriage return. The smell of rubber cement, as articles and pictures were affixed to his scrapbook pages. The riot of Al Getchell drawings, odd photos, and New Yorker cartoons above his desk.

His offbeat humor and creative energy spilling over into my child’s world: the “Ranch House,” an out-building at the Blacklick farmhouse that he fitted with newspaper negatives for wallpaper, a collection of kooky hats (his trademark at the time), a child-sized drum set and a big picture of a red-fruit-encased woman that said, “Life Is Just A Bowl of Cherries.”

He rigged up a swing on the catalpa tree, painted it turquoise and then hot pink (it matched the front porch both times). In the fall he made me a house of cornstalks.

He grew incredible sweet corn, asparagus, strawberries, gourds, and beans. We had a lot of company in the summertime to help us eat it. He grew a splash of flowers; hollyhocks were my favorite, as I made them into doll skirts. We loved Queen Anne’s lace.

He taught me the names of flowers, both wild and domestic, birds, trees, and fish. We hiked to the woods to visit the dwarf’s house in a hollow tree. I really believed it. He read me books in various voices with dramatic intonations.

He was just at home in downtown Columbus. I spent countless hours in restaurants (I befriended bartenders, waiters, and waitresses, naming my dolls after the latter), theaters, openings, and press parties. We had free passes to everything.

I accompanied him to museums, art galleries, graveyards, historic sites, visiting old-timers and celebrities. I spent a lot of time on local early television. The lights were bright and I had to squint as I was instructed to “look at the red light and wave.” My biggest thrill was meeting Roy Rogers.

Columbus was a fairyland to me, full of parks, flowers, fountains, the Ohio State Fair, fun rides, old mansions, a re-blooming German Village, hearty dinners, fancy buffets, beautiful people and characters of all ages. They wanted to talk to my father, and he listened to them, folded copy paper and ball-point pen in hand.

He rarely got to eat his dinner in a restaurant without interruption. He never made it down a city block without being recognized and given a news tidbit or two.

After I went to college and for twenty-four years thereafter, he wrote me a letter a week, filling me in on a Columbus that was changing rapidly. On my trips home we had an exchange; I fixed his favorite foods, like cornbread and potato salad and he told me stories about Noble County and Columbus.

We had our favorite topics; Chautauqua, revival meetings, medicine shows, riverboat theater, characters from his hometown, Columbus characters, art, dreams (we both dreamed in color with many scenes per night).

He would yell out words when there was a lull, often the punchline of a recent story or “Habiba!” (the name of a belly dancer at Benny Klein’s), “Excelsior!” (from the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem of the same name) or “Are you all right, Roy?” (once Dale Evans had said this while hitting her cowboy husband with her Stetson hat).

Ben Hayes’ One Hundredth Birthday, April 1, 2012

By: Christine Hayes

Ben Hayes

Ben and Christine enjoying a summer afternoon

The sound of his Underwood: keys punched, the bell, carriage return. The smell of rubber cement, as articles and pictures were affixed to his scrapbook pages. The riot of Al Getchell drawings, odd photos, and New Yorker cartoons above his desk.

His offbeat humor and creative energy spilling over into my child’s world: the “Ranch House,” an out-building at the Blacklick farmhouse that he fitted with newspaper negatives for wallpaper, a collection of kooky hats (his trademark at the time), a child-sized drum set, and a big picture of a red-fruit-encased woman that said, “Life Is Just A Bowl of Cherries.”

He rigged up a swing on the catalpa tree, painted it turquoise and then hot pink (it matched the front porch both times). In the fall, he made me a house of cornstalks.

He grew incredible sweet corn, asparagus, strawberries, gourds, and beans. We had a lot of company in the summertime to help us eat it. He grew a splash of flowers; hollyhocks were my favorite, as I made them into doll skirts. We loved Queen Anne’s lace.

He taught me the names of flowers, both wild and domestic, birds, trees, and fish. We hiked to the woods to visit the dwarf’s house in a hollow tree. I really believed it. He read me books in various voices with dramatic intonations.

He was just at home in downtown Columbus. I spent countless hours in restaurants (I befriended bartenders, waiters, and waitresses, naming my dolls after the latter), theaters, openings, and press parties. We had free passes to everything.

I accompanied him to museums, art galleries, graveyards, historic sites, visiting old-timers and celebrities. I spent a lot of time on local early television. The lights were bright, and I had to squint as I was instructed to “look at the red light and wave.” My biggest thrill was meeting Roy Rogers.

Columbus was a fairyland to me, full of parks, flowers, fountains, the Ohio State Fair, fun rides, old mansions, a re-blooming German Village, hearty dinners, fancy buffets, beautiful people and characters of all ages. They wanted to talk to my father, and he listened to them, folded copy paper and ball-point pen in hand.

He rarely got to eat his dinner in a restaurant without interruption. He never made it down a city block without being recognized and given a news tidbit or two.

After I went to college and for twenty-four years thereafter, he wrote me a letter a week, filling me in on a Columbus that was changing rapidly. On my trips home we had an exchange; I fixed his favorite foods, like cornbread and potato salad and he told me stories about Noble County and Columbus.

We had our favorite topics; Chautauqua, revival meetings, medicine shows, riverboat theater, characters from his hometown, Columbus characters, art, dreams (we both dreamed in color with many scenes per night).

He would yell out words when there was a lull, often the punchline of a recent story or “Habiba!” (the name of a belly dancer at Benny Klein’s), “Excelsior! (from the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem of the same name) or “Are you all right, Roy?” (once Dale Evans had said this while hitting her cowboy husband with her Stetson hat).

And now it is time to celebrate Ben Hayes’ One Hundredth Birthday, April 1, 2012. He left us in 1989, but we remember him and honor him by digging into Columbus history. Happy birthday, Dad. You are still loved!

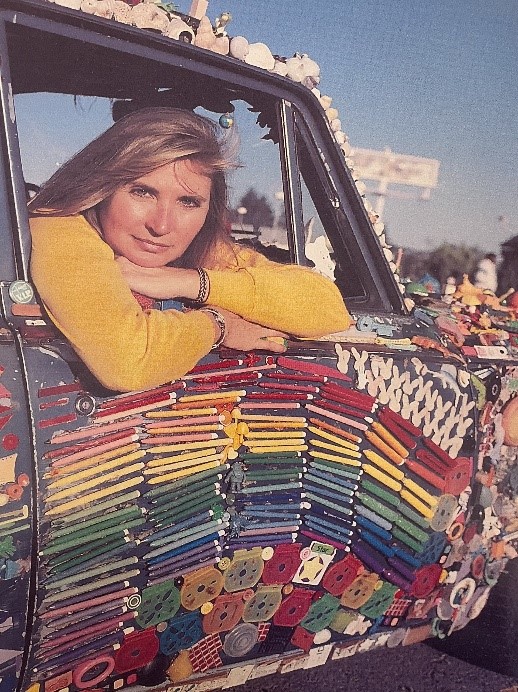

Christine was a keen observer of life, a creator of quirky and fun things such as her “art car,” a 1970s Toyota Coupe she imagined as a rolling sculpture that made its way across Northern California, where she lived for many years.

Christine was well acquainted with many of her father’s friends she met while growing up in Central Ohio. In the same Columbus Bicentennial blogspot where she celebrated her father, Ben, she also published a wonderful piece on Emerson Burkhart that we reprint here for your enjoyment.

The famous Toyota “Art Car”

Christine posing with her masterpiece

We had our favorite topics: Chautauqua, Revival Meetings, Medicine Shows, Riverboat Theater, Characters from his Hometown, Columbus Characters, Art, Dreams (we both dreamed in color with many scenes per night).

He would yell out words when there was a lull, often the punchline of a recent story or “Habiba!” (the name of a Belly Dancer at Benny Klein’s), “Excelsior!” (from the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Poem of the same name), or “Are you all right, Roy?” (once Dale Evans had said this while hitting her Cowboy Husband with her Stetson Hat).

And now it is time to celebrate Ben Hayes’ One Hundredth Birthday, April 1, 2012. He left us in 1989, but we remember him and honor him by digging into Columbus History. Happy Birthday, Dad. You are still loved!

Christine was a keen observer of life, a creator of quirky and fun things such as her “Art Car,” a 1970s Toyota Coupe she imagined as a rolling sculpture that made its way across Northern California, where she lived for many years.

Christine was well acquainted with many of her Father’s Friends she met while growing up in Central Ohio. In the same Columbus Bicentennial Blogspot where she celebrated her father, Ben, she also published a wonderful piece on Emerson Burkhart that we reprint here for your enjoyment.

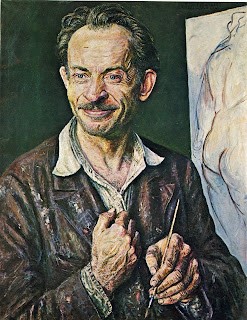

Emerson Burkhart, Painter

By Christine Hayes

It is never easy to capture Columbus Artist Emerson Burkhart on paper. My father, Ben Hayes, and Tom Thomson, both Writers and Naturalists, have their individual Memoirs of their friend. Doral Chenoweth, Jr. has his play, I, Emerson Burkhart, once performed at the Columbus Museum of Art with a Burkhart Look-a-like in the title role.

This I remember: Emerson’s mind ricocheted from one grandiose idea to the next, his hair tousled, arms gesticulating, his speech peppered with Poetry, Artists, and Philosophers. Burkhart cared not for small ideas or social mores. “What is Beauty?” would be a typical topic, a springboard for a discourse over a meal with his friends, or later, with his students.

Burkhart was born in 1905 in Kalida, Ohio, the son of a Farmer. His father wanted Emerson to be a Lawyer. But when he enrolled at Ohio Wesleyan, Emerson defied his father and went for the Art curriculum. At twenty, he studied painting with Charles Hawthorne in Provincetown, Massachusetts, at the Cape Cod School of Art. Hawthorne studied at the Art Students League and the National Academy of Design in New York City.

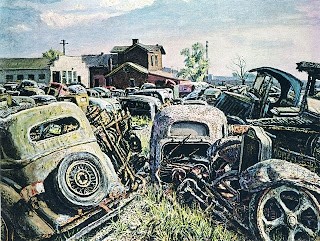

Burkhart did become successful enough to convince his father that he could make a living as a Painter. His favorite Painters were Claude Monet, George Bellows, Edward Hopper, and Albert Pinkham Ryder. He painted dark subjects such as detailed Junkyards, Cadavers, and discarded Locomotives in weed-filled Railroad Yards.

In 1955, his wife Mary Ann, whom he met in Columbus and was an Artist’s Model, died, and also Burkhart’s Brother died. It was then that Burkhart lightened up and began to paint hometown Bucolic Scenes. He always did Portraits and Self-Portraits, himself as a Miser, or laughing, or the Artist at the Easel. He did a much-admired Portrait of Carl Sandburg.

When he was asked by Karl Jaeger of Jaeger Machine Company, also Director of the International School of America, to tour the world with the Students, Burkhart painted Fishermen in the Canary Islands, Cows in India, Docks in Sweden, Antiquities in Athens, St. Peter’s in Rome, Hong Kong Harbor, the Pyramids, Tokyo. The Sky was the limit.

From the 1950’s, Burkhart had an Art Opening at his house on the same night that the Columbus Art League had their opening at the Columbus Museum of Art, which stemmed from Burkhart being denied entry for being “representational” in the Art League show, one year when it was curated by a New York Abstract Artist, Max Weber. The crowds thronged to Burkhart’s house, newspapers gushed, and Art was sold.

Burkhart’s house on Woodland Avenue had twenty-eight rooms, all huge, filled with large-scale Furniture and Oriental Rugs he bought at Auctions in Broad Street Mansions. Burkhart used the Dining Room as his Studio; it had a big North-facing window.

Judge Roy Wildermuth had lived there, and he traded the home to a Real Estate Firm for a row of Investment Houses. A member of the firm was a Burkhart Supporter and arranged for the Artist to buy it at a reasonable price during the Depression.

In the corner of the Studio was a raised platform with a Sitter’s Chair on it. Framed Paintings were stacked everywhere, against Walls, on Tables. Where there weren’t Paintings, there were Books. Paintings took up every available space on the Walls. Some Walls were painted on directly. A huge African-looking face with a light switch for an eyeball was always my favorite. When Burkhart needed to make a notation, he often wrote directly on the Wall.

Burkhart loved to paint on location and he and another Columbus Painter named Roman Johnson would often paint side-by-side. Johnson was a man who asked Burkhart for instruction. Burkhart befriended him and the only instruction was to “work every day.” Roman Johnson became a fine Artist.

Burkhart’s Portrait of Johnson is a masterpiece and is on display at the Columbus Museum of Art. Burkhart’s Portrait of Roman Johnson’s Mother, “The Matriarch,” (1944), is done in grey tones. Mrs. Cora Johnson, who was 87 when she died in 1971, sat for Burkhart forty-four times. The Artist was caught by inflation; Mrs. Johnson began sitting for fifty cents a session. She raised it to one dollar before her likeness was sombered totally.

Burkhart was also famous for his Still Life; my father chronicles Burkhart’s painting of a Basket of Fruit, from freshness to decay; a pan of live purple Catfish “Bullheads,” Lobsters, plucked Chickens, a Rag Doll, and a crude wooden mock-up of a Toy Gun. All were treated to the Burkhart eye. He often painted with a knife rather than a brush.

The Artist loved Frames; he made most of them himself, antiqued them, matched them to the subject. My father reports he would wait for Burkhart on his porch – Emerson would return from painting in the fields or in a country town, hammer the Frames onto the canvases dramatically, sometimes wrap them in brown paper and mail them before the oil paint was dry.

Emerson in his later years would spend his Birthdays sitting by the Fireplace at the Hayes house. He was fond of my mother’s Meat Loaf, Mashed Potatoes, Fruit Jello Supreme, and Pound Cake. The conversation rose to fever pitch as the night rolled on; Emerson expounding on theories for improving the City of Columbus, the state of Art and Humankind. We often went with him to Bun’s Restaurant in Delaware, too.

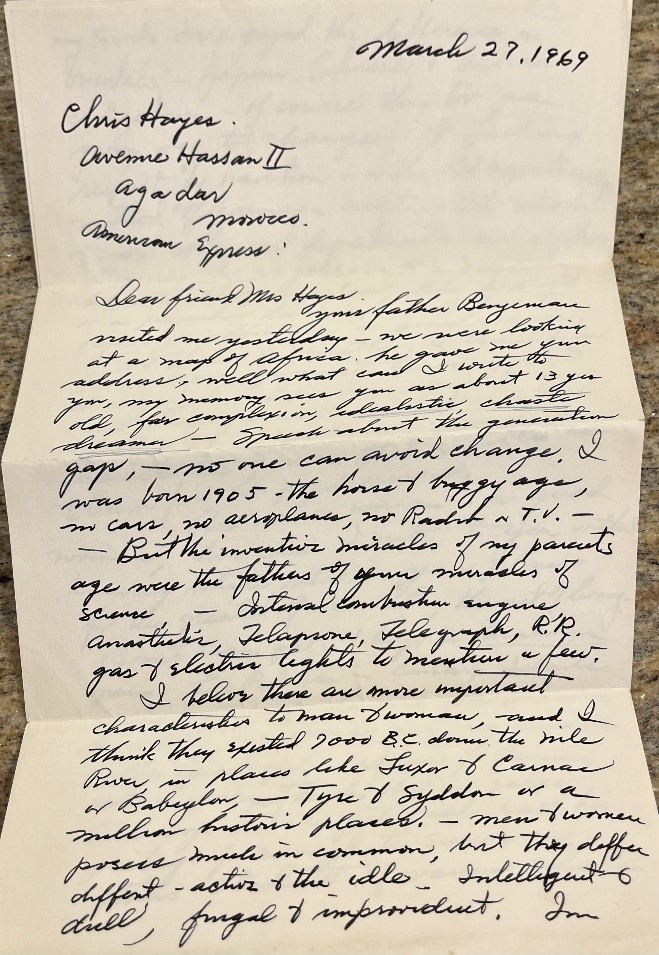

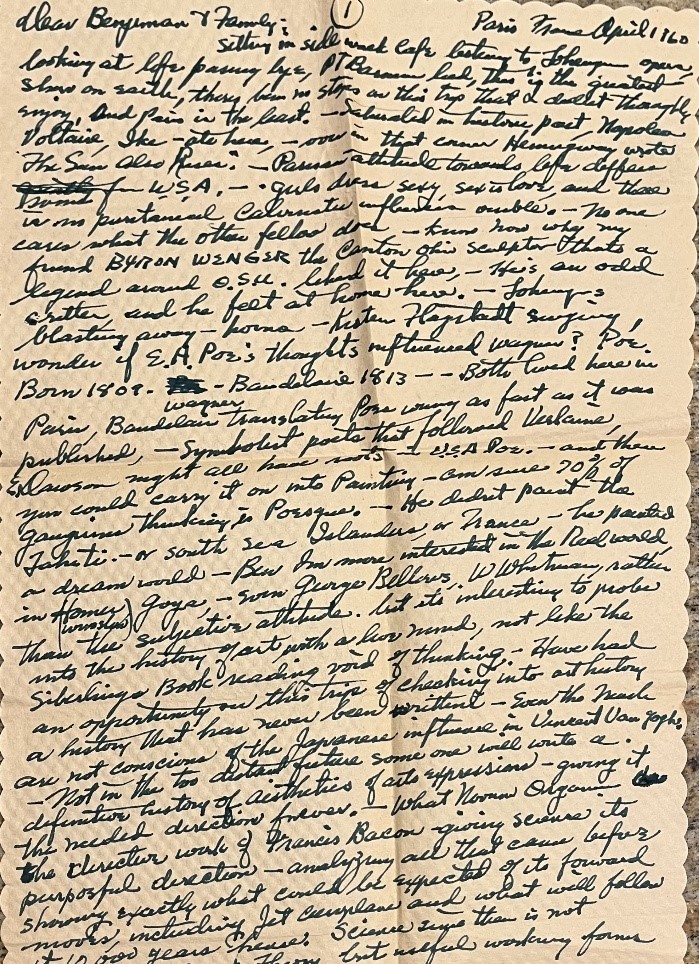

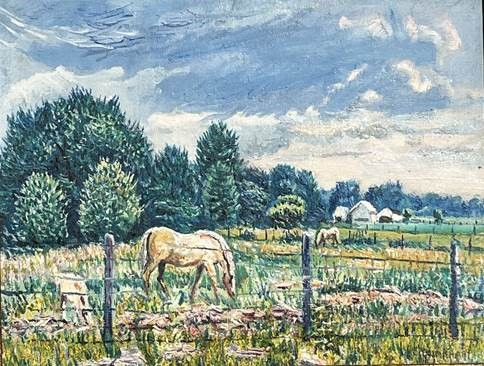

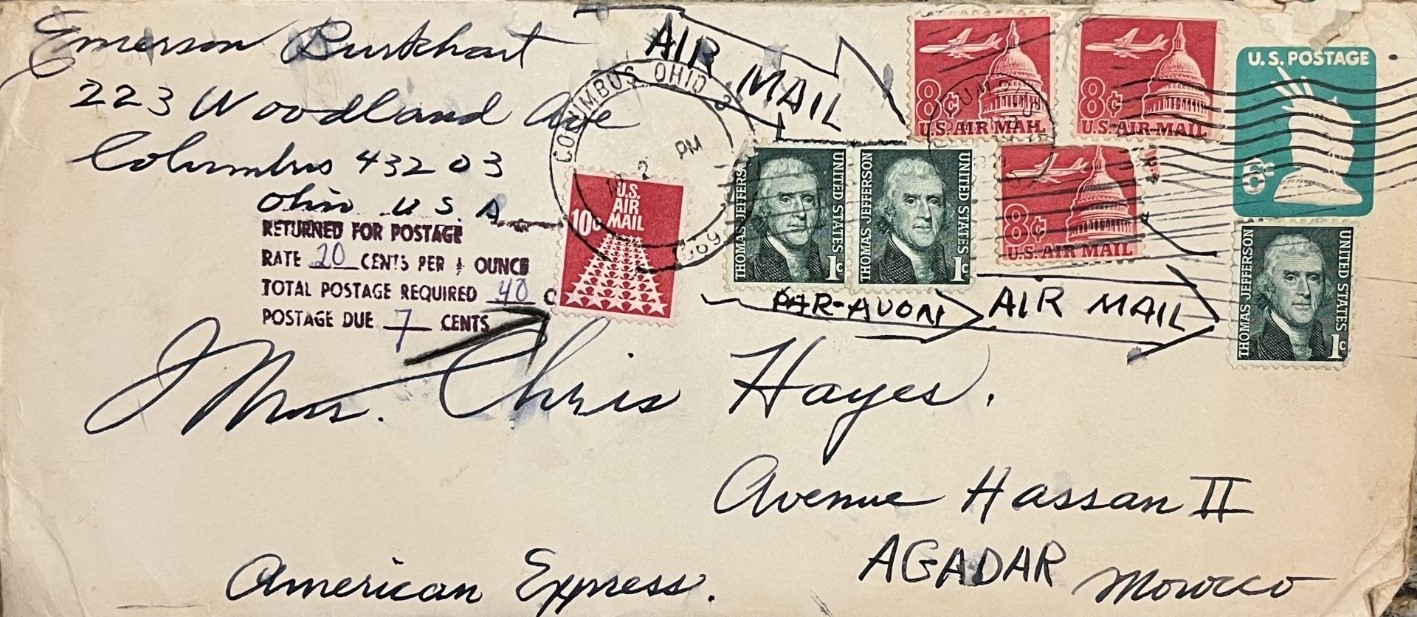

I was fond of Horses as a child and I still have a Horse Painting he gave me, among many others that he gave to my parents. I also treasure a Letter he sent me while I was in Morocco, giving me his galloping advice on how to live life to the fullest. He approved of my wanderlust. I have as well a Letter he wrote to my father from a Paris Café on two paper placemats, the penmanship florid.

I never thought of Columbus as a small town because Burkhart was in it. I did plot to leave Columbus as soon as I graduated from High School; he pointed the way to broader vistas.

Tom Thomson scattered Emerson’s Ashes over a City Reservoir after the Artist passed away in 1969. Burkhart wanted to have a little part of himself permeating the Columbus Landscape and residents. He lives on in the hearts of all he touched and his Paintings speak in their wild beauty and gentle madness.

Here is the letter that Burkhart sent to Christine Hayes while she spent time in Morocco