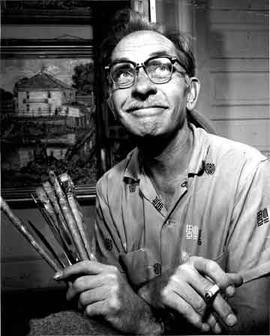

Emerson

Emerson Burkhart: Impassioned Artist, Thinker, Crusader

Emerson Burkhart was born near Kalida, Ohio in 1905. He graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1927, studied at the Art Students League in New York City, and subsequently traveled to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he took instruction from Charles Hawthorne. In 1931, he returned to the Midwest and taught at the Columbus, Ohio School of Art. He was an early member of the Ohio Art League. He moved to Cincinnati, Ohio for several years but had returned to Columbus for good by the mid-1930s.

Burkhart was a true American Regionalist and practitioner of realism, but like many artists, his style evolved over the decades. Although Burkhart never carefully catalogued his life’s work, he reported in a 1964 interview that he had painted more than 4,000 works. By some estimates, he may have produced yet another 1,000 paintings in the last five years of his life before passing away in 1969. Burkhart is well known for his often whimsical self-portraits (400+ in oil alone).

He was also a pioneer in his portraiture and documentation of African-Americans in Columbus and their neighborhoods. Burkhart was a friend to all and ethnicity played no role in how he chose his friends or subject matter for his paintings. It was highly unusual for Caucasians to depict African-Americans in their paintings at this time, yet Burkhart was doing so as early as 1941.”

This was natural for Burkhart as he was color blind and paid no attention to ethnicity. He judged people based on their character, not the color of their skin. It also helped that he lived in close proximity to their neighborhoods.

Like so many artists who came before him, Burkhart was keenly aware of what art others were producing at the time. Most artists, if not outright influenced by others, would at least dabble and experiment with styles and themes they came across. One such example is the likely intersection of Burkhart with another artist just 300 miles away in Illinois. It’s almost a certainty that Burkhart was familiar with, if not an acquaintance of, Chicago artist Ivan Le Lorraine Albright.

Albright’s best work focused on themes of aging and death, two cornerstones of Burkhart’s own exploration as an artist and eventual adoption. He took Albright’s themes to the next level with his own expressive twist of connecting them to the repeated fall over time of great empires, while predicting a similar fate for the United States.

Burkhart created masterpieces expressing his disdain for the slow death of our agrarian society, rising industrial might, the explosive growth of our Post–WWII disposable economy, and the greed that followed. He used grotesque imagery that included dead animals, human corpses, rotten food, barbed wire, and other symbols that he drove home with an uncompromising, in-your-face attitude and scalding clarity in his canvases.

Notably, Burkhart painted the only portrait of poet Carl Sandburg while he was alive. Today, it remains on display at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

He received two WPA mural commissions: one at Stillman Hall on the campus of Ohio State University, and the now-infamous mural “Dance, Drama, Music,” painted above the auditorium of Central High School in Columbus, Ohio. While the themes celebrated American artistic culture, it took only a year after its completion before the school principal had the mural whitewashed, as in his opinion it was too “risqué” and inappropriate for young minds.

The controversy of artistic censorship made national headlines and led to an American debate on the matter that was ignored by the Columbus Board of Education. It was sixty-five years later that the mural was finally restored and given a new home at the Columbus Convention Center.

An Impassioned Artist, Thinker, Crusader

If you explore Emerson Burkhart and his art, you will find that he was a complex person with strong Midwest roots. From his earliest days in Kalida, Ohio, it was clear he was destined to become an artist. As a youngster, he was given his first art lessons by a local minister who gave him pointers on drawing. Burkhart’s teachers and classmates were also aware of his talent and often recruited him to produce playbills, posters, and other artistic announcements for school activities. His brother Paul shared none of these attributes and was happy to become a farmer, just like his father.

Emerson’s father constantly pressured him to become a doctor or lawyer, but he would have none of it. He was happiest when he found time to draw or paint. In fact, one of the best days in Burkhart’s life was when he excitedly shared with his father a check for $1,000 that he received for a painting. This was a substantial sum during the Depression. As Burkhart expected, his father expressed surprise that anyone would spend that kind of money for a painting.

Additionally, he thought it more of a fluke than confirmation of his son’s artistic ability, and said, “If you can show me another check for $1,000, then I’ll be impressed.” It is doubtful the senior Burkhart was ever satisfied that Emerson had lived up to his expectations.

It was common—almost expected—that after graduation, an aspiring artist would spend time in Paris, Munich, Venice, or any of the art capitals of Europe for exposure to the cultures, and even more studies at noted European art schools. But Burkhart never followed up his formal art training with such travels.

One of Emerson’s summer school instructors, Charles Hawthorne, urged him to return to his roots and paint the truth about the region where he grew up—the Midwest. He took this advice to heart and developed himself as a Regionalist.

“J1A Dismantled” – Oil on canvas, 28 x 38 ins.

Like many artists, Burkhart’s style and subject matter changed over his career. He was deeply concerned with the human condition and rendered his interpretations of this theme throughout his life. Early on, he celebrated the best aspects of humanity, especially those which led to discoveries and improvements in the quality of life. Among these were his murals in Columbus which promoted the arts, such as the aforementioned “Music, Drama, Dance” at Central High School, and his acknowledgment of advances in the sciences, literary achievements, and more, as expressed in the murals at Stillman Hall at The Ohio State University.

During and after World War II, Burkhart began to reflect on the societal changes taking place throughout the world and especially in the United States. The Industrial Revolution was hitting its stride, and the U.S. was the unchallenged leader in global change.

During the period from 1940–1955, he was painting what would arguably be the greatest body of work he would produce in his career. He loved that America was the most charitable and powerful nation on earth, and recognized that with the Industrial Revolution, we were naturally moving away from our agrarian roots. What he feared most was that we were becoming a disposable society that thought nothing of discarding still useful material items for whatever was shiny and new.

His paintings of grand, still-operable steam-powered locomotives being cast aside, torched, and dismantled to pave the way for diesel engines reflected his literal observation and were emblematic of the broader trend he saw.

He worried that the gluttony and indulgence made possible by excess consumerism would lead us down a path to decline, one paved by the Roman, Greek, Ottoman, and British empires. To sound the alarm, he produced macabre still lifes of rotten fruits and vegetables going to waste, dead animals, withering human corpses, and skulls, woven with images of cigarette butts, coins, lobsters, and other decadent spoils of the rich.

These paintings, which would draw the eye on the basis of their subject matter alone, were all the more absorbing by the way the details, like an engine’s pistons or a coin, jumped off the canvas. To create this impasto effect, Burkhart liberally applied thick pigment by palette knife, brush, and sometimes squeezed paint directly from the tube onto the canvas.

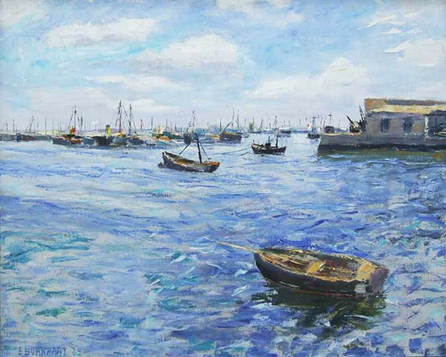

“Mediterranean Harbor Scene” – Oil on Canvas, 32 x 40 in.

Burkhart also saw this decadence in the post–World War II art world, as Realism was pushed out of the limelight and replaced by widespread interest and acclaim for Abstract Expressionism. Burkhart was no fan of “dribbles of paint” and sincerely felt that artists who produced this type of art simply didn’t have the talent to realistically portray the world around them. He would carry this grudge for the rest of his life.

His worries about American society and his ongoing battle with the art establishment were compounded by an increasingly volatile marriage and the premature deaths in 1955 of both his brother, Paul, in a farming accident, and his wife, Mary Ann, to cancer, within months of one another. Emerson was devastated by these losses. In letters to his close friend and fellow artist, Clyde Singer, Burkhart often stated how lonely he was, but that he would find a way to become artistically productive and regain his stride.

His Final Years

The next evolution of Burkhart as a painter sprang from an invitation from his primary patron and friend, Karl Jaeger. Jaeger had left his family’s industrial business to pursue his passion for education. In 1959, Jaeger founded the International School of America (ISA), a concept to take bright post-secondary students around the world for nine months of education and exposure to global culture. Jaeger persuaded Burkhart to become the school’s artist-in-residence.

During the next decade, Burkhart would take at least five trips with Jaeger and his students. This was his first direct exposure to the world outside the U.S., and he loved it. No longer was Burkhart focused on teaching America why our great culture was doomed to fail; he became interested in producing realistic impressions of people and places. His palette brightened considerably, and he typically invested much less time in each painting, opting for a looser, more impressionistic style than before.

In the last years of his life, Burkhart shared with his friends that he had no regrets about the past but planned to reinvent himself again. Nobody was really sure what he meant by that statement, but he made it clear that once the transformation took place, all of Columbus would know about it. Unfortunately, he never got the chance, as a fatal stroke felled him in November 1969.

He left behind dozens of journals in which he explored and debated with himself matters from technology and the lessons of history to the merits (or flaws) of fellow painters and writers. Sprinkled throughout are charcoal and ink sketches, self-portraits, and unlikely lists of the mundane, such as invoices and bills paid. He also kept scrupulous lists of patrons who attended his storied open houses, held annually at his home on Woodland Avenue to raise funds to support another year of work.

Burkhart will be remembered not only for the quality of his work but for the indelible impression he left on Central Ohio. He was cantankerous, opinionated, a hungry seeker and expounder of truth, and most notably—quotable! He was a favorite of the media, and he knew it.

As renewed interest continues to build around American Scene and Regionalist art and artists, Burkhart will be most remembered for producing paintings that were robust yet eloquent in their ability to convey his beliefs. He never followed the crowd and was proud to be a contrarian. He was larger than life in Central Ohio. It is doubtful we will ever see another Renaissance man like him around here again.

His paintings and prints are in a number of important museum and private collections across the United States.

The definitive biography on Burkhart, An Ohio Painter’s Song of Himself by Michael Hall, Scala Press, copyright 2009, is available through most online book sellers.

Exhibitions of Note:

The Paintings of Emerson Burkhart – A Retrospective Exhibition, November 6, 1970 – January 6, 1971, Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Columbus, Ohio

Emerson Burkhart – A Retrospective, October 11, 1985 – January 5, 1986, The Great Southern Hotel, Columbus, Ohio, curated by Mrs. Kiehner “Tibbi” Johnson

Emerson Burkhart – The Early Work, January 11 – February 16, 1986, Parkersburg Art Center, Parkersburg, West Virginia. Produced with the assistance of Mr. Jim Keny, Keny and Johnson Gallery, and Ms. Jean Robinson and Mr. Steven Rosen of the Columbus Museum of Art

Midwest Realities: Regional Painting 1920–1950, April 13 – June 17, 1995, at the Riffe Gallery, Columbus, Ohio, organized by the Southern Ohio Museum and Cultural Center, Portsmouth, Ohio

“Landscape with White House, Mountains and Lake” - 1918

This painting by Burkhart may be the earliest example of his work. Painted in 1918 at the age of 13, Burkhart gave this painting to his cousin. He had no formal training, yet one can see the potential the young man had at an early age.